Solitary, Alone & living in FEAR for 28 years . . . In the Guam Jungle: the last Japanese Soldier

Solitary, Alone & living in FEAR for 28 years . . . In the Guam Jungle: the last Japanese Soldier

January 24, 1972

A Japanese soldier was found in the jungles of Guam, having survived there for nearly three decades after the end of World War II. He was given a hero's welcome on his return to Japan - but never quite felt at home in modern society.

When American forces captured the island in the 1944 Battle of Guam, Yokoi went into hiding with nine other Japanese soldiers. Seven of the original ten Soldiers who were left behind, eventually moved away and only three remained in the region. These men separated, but visited each other periodically until about 1964, when the other two died in a flood. For the last eight years, Yokoi lived alone. He survived by hunting, primarily at night. He also used native plants to make clothes, bedding, and storage implements, which he carefully hid in his cave. He hid in the jungle, fearing he might be captured by American soldiers occupying the southern islands of Japan. No one told him the war was over.

For most of the 28 years that Shoichi Yokoi, a lance corporal in the Japanese Army of world War II, was hiding in the jungles of Guam, he firmly believed his former comrades would one day return for him.

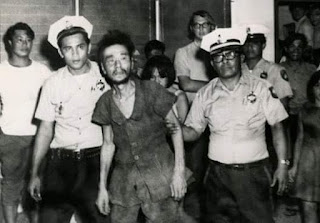

And even when he was eventually discovered by local hunters on the Pacific island, on 24 January 1972, the 57-year-old former soldier still clung to the notion that his life was in danger.

"He really panicked," says Omi Hatashin, Yokoi's nephew.

Startled by the sight of other humans after so many years on his own, Yokoi tried to grab one of the hunter's rifles, but weakened by years of poor diet, he was no match for the local men.

"He feared they would take him as a prisoner of war - that would have been the greatest shame for a Japanese soldier and for his family back home," Hatashin says.

On the evening of 24 January 1972, Yokoi was discovered by two local men checking shrimp traps along a small river on Talofofo. They had assumed Yokoi was a villager from Talofofo, but he thought his life was in danger and attacked them. They managed to subdue him and carried him out of the jungle

Yokoi later said that he expected the local men to kill him at first but was surprised when instead they allowed him to eat hot soup at their home before turning him over to the authorities. He was in relatively good health, but slightly anemic due to a lack of salt in his diet according to doctors at Guam Memorial Hospital. His diet included wild nuts, mangos, papaya, shrimp, snails, frogs, and rats

As they led him away through the jungle's tall foxtail grass, Yokoi cried for them to kill him there and then.

Using Yokoi's own memoirs, published in Japanese two years after his discovery, as well as the testimony of those who found him that day, Hatashin spent years piecing together his uncle's dramatic story.

His book, Private Yokoi's War and Life on Guam, 1944-1972, was published in English in 2009.

"I am very proud of him. He was a shy and quiet person, but with a great presence," he says.

Underground shelter

Yokoi's long ordeal began in July 1944 when US forces stormed Guam as part of their offensive against the Japanese in the Pacific.

The fighting was fierce, casualties were high on both sides, but once the Japanese command was disrupted, soldiers such as Yokoi and others in his platoon were left to fend for themselves.

"From the outset they took enormous care not to be detected, erasing their footprints as they moved through the undergrowth," Hatashin said.

In the early years the Japanese soldiers, soon reduced to a few dozen in number, caught and killed local cattle to feed off.

But fearing detection from US patrols and later from local hunters, they gradually withdrew deeper into the jungle.

There they ate venomous toads, river eels and rats.

Yokoi made a trap from wild reeds for catching eels. He also dug himself an underground shelter, supported by strong bamboo canes.

"He was an extremely resourceful man," Hatashin says.

Keeping himself busy also kept him from thinking too much about his predicament, or his family back home, his nephew said.

Return to Guam

Yokoi's own memoirs of his time in hiding reveal his desperation not to give up hope, especially in the last eight years when he was totally alone - his last two surviving companions died in floods in 1964.

Turning his thoughts to his ageing mother back home, he at one point wrote: "It was pointless to cause my heart pain by dwelling on such things."

And of another occasion, when he was desperately sick in the jungle, he wrote: "No! I cannot die here. I cannot expose my corpse to the enemy. I must go back to my hole to die. I have so far managed to survive but all is coming to nothing now."

Two weeks after his discovery in the jungle, Yokoi returned home to Japan to a hero's welcome.

He was besieged by the media, interviewed on radio and television, and was regularly invited to speak at universities and in schools across the country.

"It is with much embarrassment that I return," he said upon his return to Japan in March 1972. The remark quickly became a popular saying in Japan. He had known since 1952 that World War II had ended but feared coming out of hiding, explaining that "We Japanese soldiers were told to prefer death to the disgrace of getting captured alive.”

Hatashin, who was six when Yokoi married his aunt, said that the former soldier never really settled back into life in modern Japan.

He was unimpressed by the country's rapid post-war economic development and once commented on seeing a new 10,000 yen bank note that the currency had now become "valueless".

According to Hatashin, his uncle grew increasingly nostalgic about the past as he grew older, and before his death in 1997 he went back to Guam on several occasions with his wife.

Yokoi died in 1997 of a heart attack at the age of 82 and was buried at a Nagoya cemetery, under a gravestone that had originally been commissioned by his mother in 1955, after Yokoi had been officially declared dead.

Some of his prize possessions from those years in the jungle, including his eel traps, are still on show in a small museum on the island.

Comments

Post a Comment